How UK gambling safeguards fail to defend online punters

An Observer investigation finds Stake.com, the Australian sponsor of Everton, could be benefiting from weak controls designed to prevent British customers betting with cryptocurrency

When Everton FC’s players ran out to face bitter Merseyside rivals Liverpool last month, their shirts were emblazoned, courtesy of a £10m-a-year sponsorship deal, with the name Stake.com.

Until recently an obscure online betting firm, Stake.com, which specialises in controversial cryptocurrency gambling, has followed traditional bookmakers in hitching itself to the world’s most popular game. And football was a keen recipient of new sponsorship revenues.

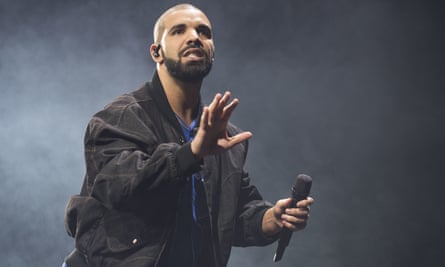

Stake has splashed plenty of cash elsewhere, too. A partnership with platinum-selling Canadian rapper Drake means his fans can watch live video streams of him gambling millions of dollars at a time. Stake has also spent big on sponsorship deals with Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) and Formula One driver Pietro Fittipaldi.

Stake’s low-profile 27-year-old co-founder, Ed Craven, has been equally lavish, spending a combined £70m on two mansions in the wealthy Toorak suburb of Melbourne, Australia, where Stake.com and its parent company, EasyGo, are based.

These extravagances are funded by the firm’s huge annual revenue, but in theory none of it should be coming from customers gambling with digital currency in the US and UK, where this is effectively banned.

However, an investigation by the Observer has found that Stake.com’s lucrative and fast-growing empire may be benefiting from lax controls on customers – including under-18s – betting with crypto.

Last month, the Observer asked Stake.com whether UK punters might be using virtual private networks (VPNs) – widely available digital tools that create a spoof location for a computer – to bypass country restrictions on crypto gambling. Stake.com said it had implemented “stringent compliance processes” to prevent this. But in tests, these processes were found to be anything but stringent.

Using a VPN, the Observer was able to access Stake.com’s crypto gambling services from a UK location within seconds.

When asked for age verification, reporters uploaded a photograph of a packet of Strepsils throat sweets instead of a legitimate form of ID such as driving licence or passport. This initially proved sufficient.

The reporters were then able to buy crypto via Stake.com, deposit it in a betting account, and proceed to lose the money on Stake.com’s slot machine games, such as Sugar Rush and Starlight Princess. It was also able to move the remaining funds into an online bank account. They could even buy crypto with one bank account and move the funds into another account, with Stake.com effectively operating as a digital currency transfer provider.

It took more than 48 hours for Stake.com to suspend the account, after spotting that a Strepsils packet was not proof of adulthood. While the company eventually cracked down on the fake ID, subsequent tests suggest an approved adult could have continued gambling with crypto, even though the Gambling Commission has yet to give any operator approval to offer such a product in the UK.

There is reason to believe that VPN crypto gambling may be vulnerable to those seeking to bet using the proceeds of crime. According to the website reporter.london, an unnamed crypto trading platform is preparing to sue Stake.com, claiming that one of its traders stole £350,000 of the digital currency ethereum and gambled it away on Stake, using VPNs.

Asked about the Observer’s test crypto bets, Stake.com said: “As with all companies in the sector, Stake.com experiences unauthorised users attempting to evade geoblocking through VPNs. Stake is aware of one account that was recently opened following the use of a VPN from the UK and the submission of false address and other false user information, all in violation of the company’s terms of service. This account was detected by Stake’s internal compliance processes and shut down.

“Stake.com utilises anti-money laundering measures on its site. Fiat to cryptocurrency exchange services are offered by third-party providers (not Stake.com), who also have their own compliance processes and requirements.” The company also offered assurances about its commitment to safer gambling.

However, one of Stake.com’s most important commercial partnerships is with xQc, a Canadian internet personality whose real name is Félix Lengyel, who has more than 11 million followers on the live video platform Twitch.

With his bombastic style and machine-gun-fire speech, Lengyel, who is 25, regularly attracts tens of thousands of viewers at a time to his streams, in which he gambles on Stake.com slot machine.

Lengyel has repeatedly stated that he is addicted to gambling, and at one stage even pledged to stop making slot machine video streams. Yet, after a brief period away from the world of betting, he signed a deal with Stake.com and returned to the fray in 2022.

Under the terms of his deal, Lengyel gets a cut when people click through to the Stake.com site via his Twitch channel. He claimed earlier this year to have funnelled $119m in bets to the company.

Like all licensed operators, Stake.com does not allow under-18s to gamble. Until now, however, anyone over 13 can watch xQc’s streams on Twitch. Last month, Twitch decided to ban casino and slots streams from its platform, naming Stake.com as one of the operators whose games it would no longer help promote. This was in response to threats from prominent streamers, some of whom had watched in horror as gambling streams began to overtake video gaming as the site’s main output.

So that was a key marketing tool lost, but Stake.com still has its high-profile sponsorship deals, including with English football teams Everton and Watford.

These deals are possible via controversial but legal “white-label” deals, under which a foreign brand that wants a presence in Britain can piggy-back on to a licence already held by a local operator, without going through its own licensing process.

Stake’s white-label deal is with Isle of Man-based TGP Europe, a business that is also the entry point for Leeds United sponsor SBOTOP, a Philippines-based online bookie, and Hull City’s deal with Kenyan-owned SportPesa. The arrangement allows Stake to offer gambling services with fiat currency (normal money) but not crypto, in the UK.

White labels are a backdoor used by some of the little-known betting firms that sponsor English football teams. The deals allow them to reach the eyeballs of football-watching punters in markets such as China and Thailand, where gambling is theoretically illegal and cannot be promoted.

But there are also questions about whether foreign firms are avoiding a moral obligation to help tackle gambling addiction in the UK. One important way in which large licensed operators such as Ladbrokes and Bet365 do this is by paying 0.1% of their winnings as a voluntary levy to the GambleAware charity.

But Stake.com is not technically the licensed operator; TGP Europe is. And last year TGP paid £2,000 to GambleAware, which would implying that its revenue was just £2m. And GambleAware’s list of donors does not mention Stake.com.

“White labels allow companies like Stake to avoid the due diligence of a licensing process, allowing them to advertise and access the British market,” said Matt Zarb-Cousin of campaign group Clean Up Gambling.

“All gambling firms should have to apply for a full licence if they want to legitimately operate here. The Gambling Commission and DCMS [Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport] should not be endorsing the white-label system, which privileges those unwilling to go through the licensing process.”

Even if Stake.com did acquire its own licence to operate in Britain, there is no guarantee that it would have much to fear from the regulator.

In August, the Guardian reported that Everton FC told Stake.com to stop using club branding in a promotion that offered a $10 free bet to anyone who wagered $5,000 in a month.

It was not a matter for the Gambling Commission though. The offer may have been cloaked in the imagery of a 144-year-old stalwart of English football but it was priced in dollars and, ostensibly, unavailable to British punters – except those who knew how to use a VPN, that is.